Menu

Landgrabbing, anywhere, is an outright denial of the farmers’ right to land, right to till, the rural and indigenous peoples’ right to self-determination and human dignity.

Landlessness and landgrabbing amid looming global economic depression

The world capitalist system is yet again confronted with another looming global economic depression.[1] With little to no recovery in more than a decade after the Great Financial Meltdown of 2008 and the subsequent food crisis,

The global rush for land that ensued following the 2008 financial crisis has not abated. On the contrary,

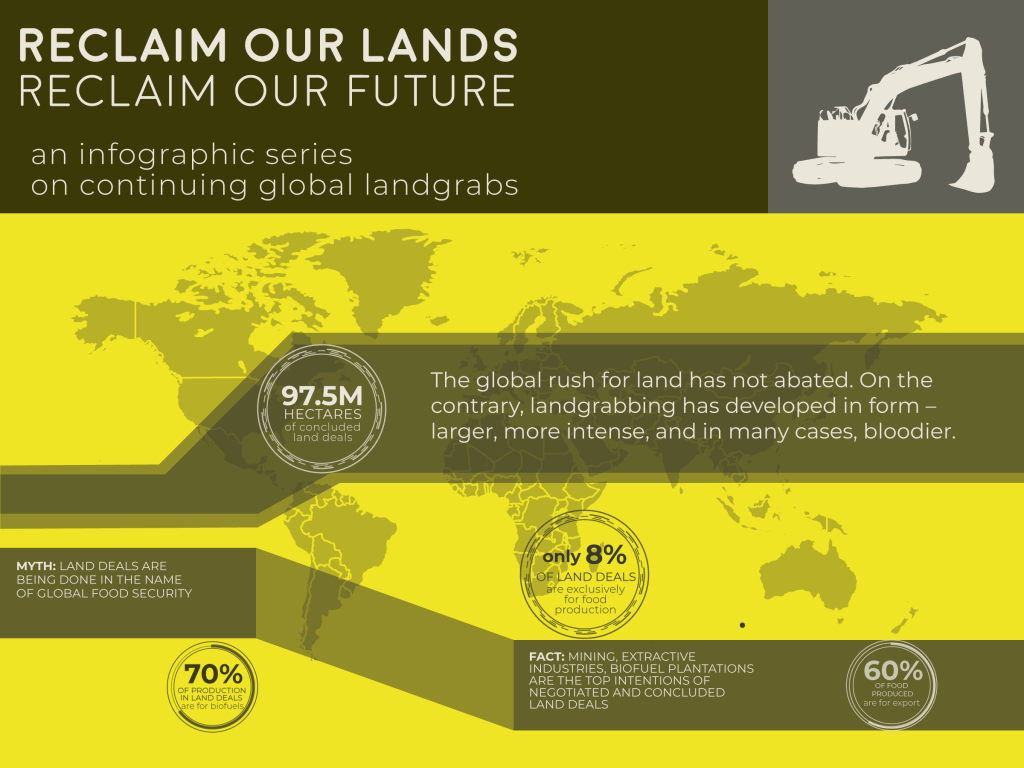

Since 2000, transnational companies (TNCs) and institutional investors have grabbed around 97.5 million hectares of land around the world in 3,158 concluded deals. More than 600 deals spanning almost 36 million hectares are further being negotiated –totaling 133 million hectares of land sold and leased to foreign and domestic investors.[3]

Table 1. Top Target Countries and Global Hunger Index*

| LM Rank | Countries | GHI Rank | GHI |

| 1 | Peru | 35 | 8.8 |

| 2 | Congo, Dem. Rep. | 116 | 38 |

| 3 | Ukraine | 15 | <5 |

| 4 | Brazil | 31 | 8.5 |

| 5 | Russian Federation | 21 | 6.1 |

| 6 | Philippines | 69 | 20.2 |

| 7 | Indonesia | 73 | 21.9 |

| 8 | Sudan | 112 | 34.8 |

| 9 | Argentina | 18 | 5.3 |

| 10 | Mozambique | 102 | 30.9 |

| 11 | Madagascar | 116 | 38 |

| 12 | South Sudan | 116 | 38 |

| 13 | Papua New Guinea | 97 | 29.7 |

| 14 | Liberia | 108 | 33.3 |

| 15 | Congo, Rep. | 99 | 30.4 |

| 16 | Ethiopia | 93 | 29.1 |

| 17 | Sierra Leone | 114 | 35.7 |

| 18 | Guinea | 92 | 28.9 |

| 19 | Cambodia | 78 | 23.7 |

| 20 | Malaysia | 57 | 13.3 |

| 21 | Myanmar | 68 | 20.1 |

| 22 | Tanzania | 95 | 29.5 |

| 23 | Guyana | 55 | 12.6 |

| 24 | Zambia | 115 | 37.6 |

| 25 | Central African Republic | 119 | 53.7 |

| 26 | Ghana | 62 | 15.2 |

| 27 | Cameroon | 71 | 21.1 |

| 28 | Pakistan | 106 | 32.6 |

| 29 | Gabon | 63 | 15.4 |

| 30 | Uruguay | 15 | <5 |

*countries in emergency status without a GHI designated rank were given 116 and 38

At the heart of these massive

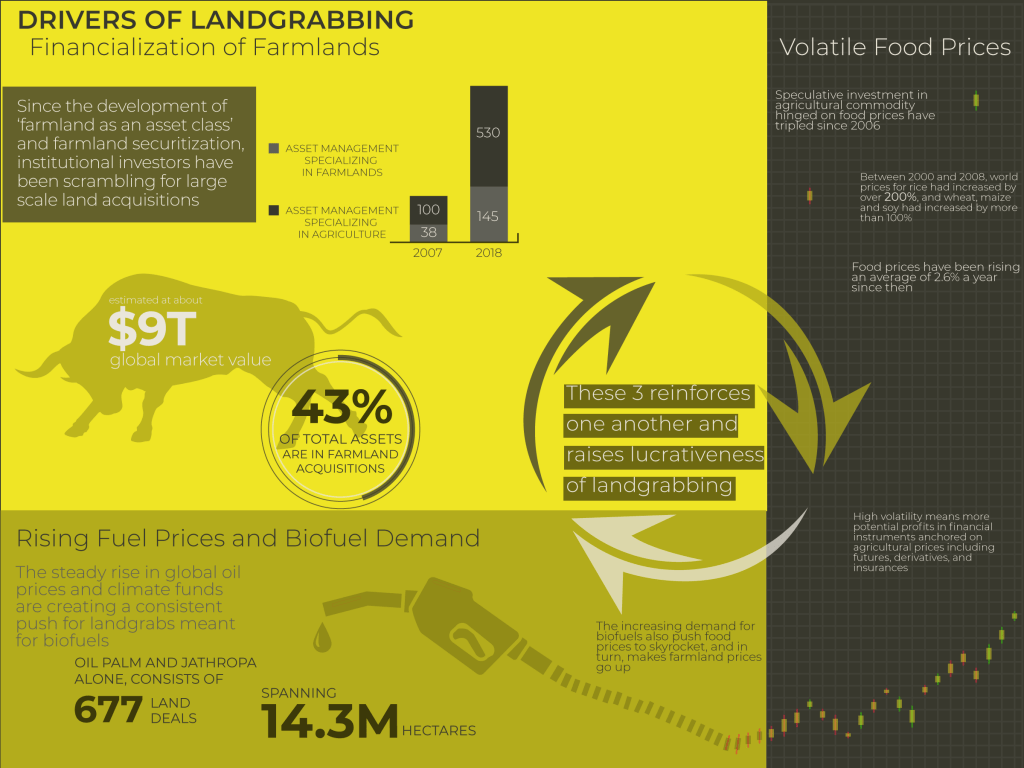

In more than just a decade, investment funds specialized in the broad food and agriculture sector jumped from 100 in 2007 to 530 by October 2018, amounting to an aggregate US $83 billion.[4] Those specializing in farmland acquisition and management leaped from 38 in 2007 to 145 over the same period –

Large scale foreign landgrabs happen mostly in the most food insecure of developing nations. While most of the land deals preclude global food security, only 8% of these land deals are exclusively for food production[6] and 60% of this small portion still are

Most of these land deals – around 70% – are reserved for biofuel production, an industry bound

While these large scale

International finance institutions (IFI) and development finance institutions (DFI) play a key role in global landgrabs

IFIs and DFIs are reshaping land policies undermining food sovereignty and denying land rights to farmers. For decades, the IMF-WB Group have imposed market colonialism and economic genocide through conditional loans, with the IMF shadow program/advisory services as prerequisites. Not only do they fund private agribusiness ventures

For instance, in 2017, the WB has included land laws and regulations among the indicators of its Enabling the Business of Agriculture (EBA) project, which ranks countries according to friendliness to agribusiness. According to the World Resources Institute, regulatory and policy frameworks as they are favor investors over communities in land formalization processes in every step of the way.

Trends of corporate capture in global aid and development financing have prompted the rise of DFIs – banks providing financing to financing to private corporations, including TNCs, supposedly for development goals. Yet in many cases, DFIs have, directly and indirectly, financed

National development agendas in developing countries continuously veer away from substantive and redistributive land reform programs. In response to market pressures and loan conditionalities, many developing countries continue to restructure land policies to accommodate foreign investments, which in many cases partner with the local landed elites. This further aggravates landlessness and rural peoples’ dispossession.

In Burma, the amendments made to

In Brazil, President Jair Bolsonaro’s very first order as soon as he assumed

In Zimbabwe, thousands of families from eight provinces face forced eviction to give way to the construction and operations of a number of

The US, China, Canada, as well as Malaysia and the United Kingdom are leading the charge in stealing lands from farmers, indigenous peoples

In the last few years though, China has launched a massive land grab spree under the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) – a debt-trap initiative to bolster China’s influence in Asia, Europe and Africa – that it has earned the second spot, next to

Vast tracts of land in the Global South, largely for infrastructure development, are being held and controlled by Chinese companies through conditional loans with developing countries. In Sri Lanka, the 99-year lease of Hambantota Port and the construction of the Colombo Financial City are brandishing through existing land laws, dispossessing farmers.

Military intervention, proxy wars, man-made famine, and civil wars aggravated by resource grabbing catalyzes forced rural dispossession and landlessness

Following the2009 food crisis and land rush, the number of hungry people on the planet surpassed 1 billion[16] — most of which are rural peoples. Despite the posturing of

Most of the countries in food crises for the past five years, such as South Sudan, the Democratic Republic of Congo, Bangladesh, Pakistan, and Ethiopia to name a few, are among those with the largest land deals and cases of

People in crisis level hunger are concentrated geographically in West Asia and

In Yemen alone, around 22.2 million of the 29 million population are in need of humanitarian assistance.[19]

In Palestine, the March of Great Return is close to marking its first year. By the 48th week of the Palestinian peoples’ assertion of their right to return, Israeli forces have killed more than 250 and injured over 26,000 from their ranks.[21] Sixteen were killed in West Bank and Gaza in the past two months – since the start of 2019 – and seven of them were children.[22] The UN Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees has registered a total of 5.4 million Palestine refugees due to the Israeli occupation.[23]

Fascism and militarism are on the rise to hasten landgrabs and protect foreign and domestic elite’s investments.

In the Philippines, the deadliest country in Asia for peasants, a total of 182 farmers were politically killed under the fascist regime of President Rodrigo Duterte. The latest was the murder of Roberto “Bobby” Mejia, a peasant leader in Pangasinan province who was among the organizers of the

Day of the Landless – a call for solidarity

Today, the fundamental problem of landlessness in many rural communities is being ignored, obscured, or even trivialized by many international, intergovernmental, and national

Rural communities around the world are rising against landlessness. In

As the bitter lessons of peasant movements in the global south

[i] The new kinds of investment products that financialization has encouraged provide an avenue for large-scale financial investors to pour huge amounts of money directly into financial products that encourage the acquisition of land in developing countries, often for the production of biofuels.

[ii] In Guinea, IFC has financed resource extraction projects amounting to US $140M in loans that resulted to the displacement of 150,000 people, while hundreds of thousands more face the risk of cyanide pollution in their water sources. Similarly, IFC has funded mining operations in Burma that displaced 16,000 farmers and indigenous Karen peoples in 23 communities.

[iii] Institutional investors include insurance companies, pension funds, mutual funds, hedge funds, sovereign wealth funds,and university and foundation endowments

[iv] China leaning research group China Africa Research Initiative

[1] http://fortune.com/2018/09/13/jpmorgan-next-financial-crisis/

[2] https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2019/02/how-to-rebalance-our-global-system/

[3] LandMatrix.org 2018

[4] Impact Investing in the global food and agricultural investment space. Valoral Advisors. November 2018

[5] Global Food and Agriculture Outlook. Valoral Advisors 2018

[6] LandMatrix.org 2018

[7] Global Landgrabs: Beyond the Hype. Kaag and Zoomers. 2016

[8] Global Food and Agriculture Outlook. Valoral Advisors. 2018

[9] Database. IFC and Sub-investment in FIs. Inclusive Development International. 2017

[10] https://www.mmtimes.com/news/myanmars-land-law-ticking-time-bomb.html

[11] https://www.reuters.com/article/us-myanmar-landrights-lawmaking-feature-idUSKCN1QF03Y

[12] https://www.theguardian.com/world/2019/jan/02/brazil-jair-bolsonaro-amazon-rainforest-protections

[13] http://www.hlrn.org/img/cases/Zim_evictions_final.pdf

[14] LandMatrix.org 2018

[15] Ibid.

[16] FAO 2011

[17] FAO 2018

[18] LandMatrix.org 2018

[19] http://foodsov.org/stop-starving-yemen/

[20] https://www.savethechildren.org/us/about-us/media-and-news/2018-press-releases/yemen-85000-children-may-have-died-from-starvation

[21] https://www.middleeasteye.net/news/israeli-forces-kill-palestinian-boy-and-wound-others-during-gaza-protest

[22] https://electronicintifada.net/content/palestine-pictures-february-2019/26801

[23] https://www.unrwa.org/sites/default/files/content/resources/unrwa_in_figures_2018_eng_v1_31_1_2019_final.pdf

[24] https://www.facebook.com/saka.pilipinas/photos/a.110758739546395/323144704974463/?type=3&theater