Menu

A grassroots international coalition from the Global South warned Wednesday that the unprecedented food price spikes are already causing massive landgrabs as institutional investors flock to safer assets.

The People’s Coalition on Food Sovereignty (PCFS) called for “renewed international cooperation” to defend rural people’s rights to land and livelihood amid rich countries’ scramble for land.

“Signs are pointing to a massive increase in landgrabs and resource grabs that are redolent to the past food crises of 2008 and 2011, with the lives and livelihood of the already impoverished rural peoples on the line,” said Chennaiah Poguri of PCFS Asia.

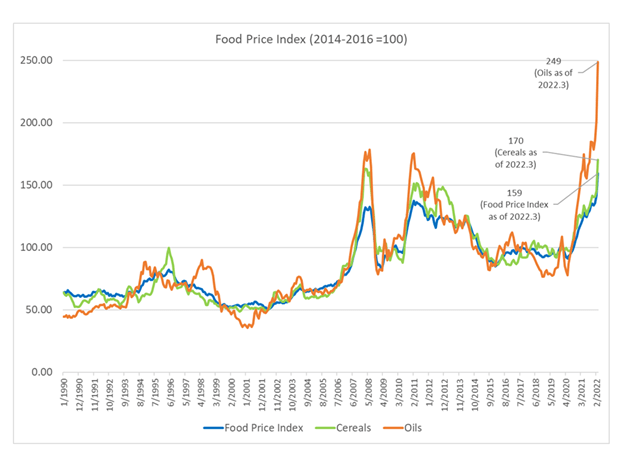

Global food prices have risen by 39.7% in just a year, reaching their highest point since the 2011 food crisis. In some developing countries like Sri Lanka, Brazil, Indonesia, and India, basic food prices have jumped much higher – pushing more and more people in the Global South into starvation.

PCFS demands that all countries’ governments protect all agricultural and food-producing lands from landgrabs in the name of development. Rural peoples in the Global South are calling for an end to food shortages by recognizing their inalienable right to own and manage common property resources such as land, water, and forests.

In a published article, the Coalition pointed out that the same drivers of the 2008 and 2011 food crises—fuel price spikes, financial speculation, and imperialist wars—are propping up food prices in 2022. The scramble for land resurfacing today is redolent of the two most recent food crises, resulting in food uprisings in more than 30 countries. Already, uprisings in Sri Lanka, Pakistan, and Egypt have shown stark similarities with massive food price-related protests in 2008.

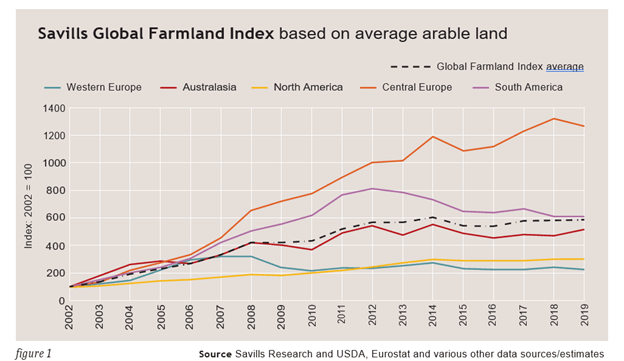

Farmland prices have peaked higher in the past few decades, prompting a 122% increase in the number of transnational land deals in the Land Matrix database from 2011-2020.

“The United Arab Emirates (UAE), Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, and China snapped up wheat and other grain futures last year, prompting land disputes in India, Pakistan, Cambodia, and Indonesia,” said Poguri, who is also the chairperson of the Asian Peasant Coalition.

In the last few months, numerous African countries including Tunisia, Guyana, Tanzania, and Sudan have signed new agreements with rich countries like the UAE and Saudi Arabia for food export production and land leasing. An agricultural company in Pakistan also recently signed a $1 billion deal with Chinese and Saudi Arabian companies, which will allow the country’s exports to grow.

“A longstanding free-for-all in acquiring farmlands, relaxed monetary policies, and enabling trade regimes have coddled and encouraged the land accumulation of transnational companies, especially in the Global South,” Poguri said.

He added that the global rise in land inequality, land concentration in the hands of the wealthy, and landlessness have made rural food producers the most vulnerable to hunger, food price shocks, conflict, and poverty. Small farmers, agricultural workers, and landless peasants now make up more than two-thirds of the world’s extremely poor.

Last year, a report from the International Land Coalition revealed that “land concentration is much worse than we know,” and the trajectory is leading to a few landlords and companies operating farmlands in poor countries.

Smallholder farmers account for 84% of all farms worldwide yet operate only around 12% of all agricultural land. Meanwhile, landlords—owning the largest 1% of farms in size—use over 70% of the global farmland.

“History repeats itself, first as tragedy, second as farce. Third, however, as a call-to-arms. Rural peoples must unite to resist these new schemes of landgrabs and hold accountable those enabling plunder,” Poguri ended. ###