Menu

The people in Sri Lanka are experiencing massive fuel shortage, skyrocketing food and goods prices, and routine power shortages. Massive protests have emerged, and the government is reacting violently, several people have been killed and hundreds more wounded.

With massive debt and economic decline on his heels, Prime Minister Mahinda Rajapaksa, elder brother of President Gotabaya Rajapaksa, resigned from office last May 9, ending their nearly 20 years of dictatorship.

Protester holds Gota Go Home slogan in Colombo

Protests, however, continued despite the new PM Ranil Wickremesinghe swearing into office as he’s seen as someone close to the Rajapaksas and don’t offer the changes the activists demand.

Last week, Colombo officially defaulted on its debt to the World Bank and asked the IMF for a US$5.4 billion bailout. The IMF then forced Sri Lanka to take on austerity measures including budget cuts for social services, revision of taxes in exchange for more loans.

With massive debt distress being pointed as the major culprit of the current crisis, what’s happening in Colombo may spell a blueprint for similarly debt-distressed nations.

Several other countries, including Nigeria, India, Kazakhstan, Egypt, and Pakistan are highly likely to spiral down in the same way due to their large food inflation as well as increased debt servicing in the past 2 years.

“Gota Go Home” became the resounding call of the people’s actions since early 2022. The demand that Gota and his family steps down is central to these widespread unrest in Colombo and elsewhere.

Massive protests have emerged in the streets of Colombo and other major centers of Sri Lanka, estimated to have peaked at tens of thousands. The massive actions have started in early May as food, fuel, and medicine shortages, including 13-hour scheduled power shortages, disrupted the lives of most Sri Lankans.

Rajapaksa home torched by protesters

At the eve of the Rajapaksa resignation, protests from rural sectors as well as opposition forces merged in Colombo at the doorsteps of the PM. Rallying people were violently dispersed by over 20,000 so-called hired thugs and thousands of police forces.

Nine people died in what amounted to a violent, state-initiated crackdown. At least 78 persons were sent to the hospital, with 200 more injured. Protesters set the PM’s home of origin on fire in response, and Rajapaksa needed to be rescued by the Sri Lankan military to escape.

Despite the new PM, protests continue in the capital and elsewhere as the crisis continues to put the lives and livelihood of the people of Sri Lanka in peril.

For months since the end of 2021, Sri Lankans have been forced to wait in long lines to buy essentials such as medicines, fuel, cooking gas and food.

In January, headline inflation for food has reached 21%, including vegetables, rice and green chilies.

In February, rice prices have jumped to 500 rupees (USD 1.40) a kilo. Milk powder, including baby milk, have skyrocketed to 790 rupees for 400 grams.

In April, the National Consumer Price Index increased 33.8 percent year-on-year, more than six times the 5.5 percent increase reported the previous year. Estimates suggest that the cost of 3 meals a day jumped to 2000 rupees (USD 5.5) in April and up to 3000 rupees (USD 8.2) if there’s meat. With a common daily wage of 1,500 rupees (USD 4), most of the wage laborers and rural workers don’t have enough to feed their families.

Transport fares have also increased by 70%, official estimates suggest, creating a feedback loop of upward spiraling sticker price of basic goods. By May, the fuel shortage had gotten so worse that the government mandated a cap on the amount of gasoline a single household can buy. About a third of small fisher folk, according to the National Fisheries Solidarity Movement (NAFSO), have deliberately stopped their operations due to the cap on fuel supply.

In northern and east Sri Lanka, hordes of families, including the indigenous Tamil Nadu, are in an exodus to India to evade the massive food crisis in the country.

The Rajapaksa family is a political dynasty that has ruled the country for almost 20 years now.

A kleptocracy built atop genocides of Tamil people, Gotabaya was a former secretary to the defense ministry responsible for the death of at least 100,000 people before the 2009 ceasefire.

During his rule, Sri Lanka also moved closer to China, borrowing almost $7bn for infrastructure projects, many of which turned into white elephants mired in corruption.

His brother, Mahinda has served as president when the Tamil genocide happened. He also served twice as prime minister since then. Their rule routinely characterized as a “soft dictatorship” and the brothers as “semi-authoritarian” figures, the Rajapaksa government consistently wages suppression campaigns against progressives, opposition, and minority groups.

In their near 20 years of reign, their two other siblings, Chamal R and Basil R, have also become kingpins of port management, agriculture, and finance in the country. Son of Mahinda R, Namal R as the Sports and Youth Minister and also Son of Chamal R as the State Minister of Agriculture which counts over 70% of national budget allocations. Other government posts were also given to at least a dozen more cousins and in-laws over the course of the decade since they took power.

During his rule, Sri Lanka also moved closer to China, borrowing almost $7bn for infrastructure projects, many of which turned into white elephants mired in corruption.

Massive youth protests that started to swell in April forced Rajapaksa’s government to give concessions, taking out some of their family members from the cabinet to appease the uprising. The people, however, did not back down and continued the protest, becoming more militant by the day. Church groups, monks, opposition groups, and other sectors converged in Colombo and propped up protests in other provinces in the country.

By May 9, the then PM Mahinda R brought around 5000 supporters to Temple Trees, the residence of Prime Minister and mobilized to attack peaceful protestors. The government-backed thugs attacked the peaceful show of resistance.

On May 10, PM Rajapaksa resigned officially and was replaced by Ranil Wickremesinghe, one of their close allies.

As of writing, June 1, protests continue on their 54th day to demand their fundamental rights to food, freedom, and democracy in Colombo.

When Gotabaya Rajapaksa was elected in 2019, he made good on his promise to implement tax cuts, which experts note, cut down at least 25% of the government’s revenue. The new tax package cut the value added tax to 8% from 15% and the so-called nation building tax of 2% for businesses.

A severe shortage of foreign currency has left Rajapaksa’s government unable to pay for essential imports, including fuel, leading to debilitating power cuts lasting up to 13 hours.

A policy of convenience, Rajapaksa also introduced import bans in early 2020 to reel in foreign reserve expenditure. This includes auto parts and among others, synthetic fertilizer. This is despite the promise of increased subsidies to provide fertilizer free of price when he ran for office in 2019.

Sri Lanka’s Ceylon tea industry, which accounts for at least 2% of its GDP and a major source of its foreign reserves, took a nose dive in 2020 as prices went down dramatically. The ban in fertilizer imports in 2021 halved its output, which greatly reduced dollar revenues.

With the general inflation rate nearing 19% in early 2022, the Rajapaksa government made announcements in April 2022 that it cannot pay for the upcoming principal payments.

This was followed with a downgrade of its credit ratings from institutional lending graders such as Fitch, which tightened the noose on its already choking economy.

According to Fitch’s estimates,

“We believe it will be difficult for the government to meet its external debt obligations in 2022 and 2023 in the absence of new external financing sources. Obligations include two international sovereign bonds of USD500 million due in January 2022 and USD1 billion due in July 2022. The government also faces foreign-currency debt service payments, including principal and interest, of USD6.9 billion in 2022, equivalent to nearly 430% of official gross international reserves as of November 2021.

The Sri Lankan government faces international sovereign bond maturities of US$500 million in January 2022 and US$1 billion in July 2022.

Despite the Rajapaksa government’s outward reluctance to receive aid from the IMF earlier this year, they have requested a US$5.4 billion bailout from the institution, which it denied. By late May, the IMF had started negotiating with the new Governor of the Central Bank of SL government to implement conditions in exchange for a debt restructuring package.

Interviews with financial and economic experts from the IMF and WB say that the crisis is one of a political nature and is mainly a mismanagement problem. Major causes outlined in these narratives include the tax cuts that the Rajapaksa government have done in early 2020, which decreased its government’s revenue by 25%. Another major issue, according to economists, is the increase in debt incurred amid the pandemic despite the major loss in their dollar reserves in 2021.

Another less talked about but popular narrative includes blaming the current food crisis to the 2021 ban on synthetic fertilizer imports in the country. This, according to the media and some NGOs, has halted at least 20% of smallholder farmers around Colombo from farming in early 2022. By now, due to the fuel crisis, 1/3rd of small boats keep idling in the anchorage points or in the coasts, which causes unemployment, income loss and job insecurity to fisher families.

Business forums and media are also buzzing about the increased likelihood of privatization in the country, following the restructuring conditions of the IMF bailout. One key industry on the table is the airline industry, which many investors from India and elsewhere are bidding on.

Then there’s the China debt narrative. The media has been covering opinions that the massive debt from the Belt and Road Initiative projects have triggered the current crisis, especially with the Rajapaksa regime known to be a stalwart of Chinese influence in the region.

One aspect not largely covered, however, is the fact that foreign reserves of Sri Lanka are massively reliant on tourism, agricultural exports, and migrant remittances—all of which have dried up since the pandemic.

Sri Lanka was also deemed ineligible for the massive debt-relief program of the G20 last year, the Debt Service Suspension Initiative (DSSI). The IMF has flogged the Sri Lankan government for reneging on its promises to implement major austerity measures and privatization projects to keep its debt to “sustainable” levels.

A deeper look into the ongoing food crisis will also point to the two-decade transition towards a so-called service economy, coupled with massive cuts of government support to agriculture and fishing. This, together with the lucrative privatized food import contracts from India and China, have crippled the country’s domestic food production.

A radical departure from their neoliberal economic system is the minimum requirement to pull out of the crisis.

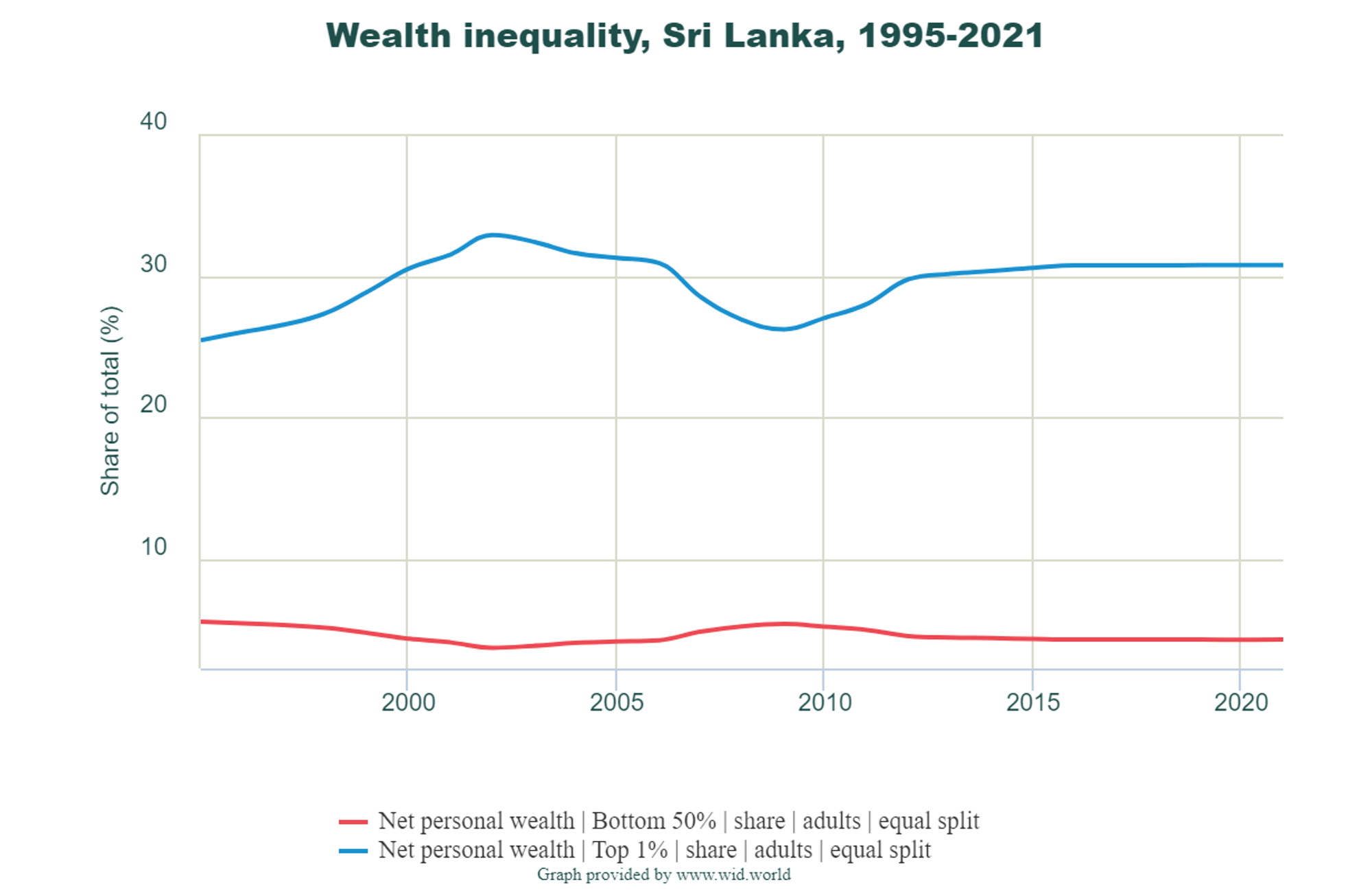

A highly unequal country, the post-war economy of Sri Lanka saw at least 31% of national wealth in the hands of the richest 1%, over six times the combined wealth of the bottom 50%.

So while most of the upper crust of society have shut themselves in their lavish mansions or fled the country, the bottom half—even the next 40 percentile—are suffering the aftermath of their profiteering.

What’s clear for the protesters and progressive groups in Sri Lanka right now, however, is that a nominal change in government is not enough. A radical departure from their neoliberal economic system is the minimum requirement to pull out of the crisis.

⌛ See how the crisis unfolded in this timeline. Click on the arrow to expand.